A recent IMF paper provides further evidence that the return on investment of conflict prevention can be substantial.

The relationship between macroeconomic policy and armed conflict remains a largely underexplored area of research. This gap persists despite the high stakes: the number of armed conflicts is at an all-time high, with devastating human and economic consequences. Globally, efforts to prevent conflict have too often fallen short. However, new research from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), recently presented at the Department of Political and Peacebuilding Affairs (DPPA), offers fresh evidence and compelling arguments in support of more effective prevention strategies.

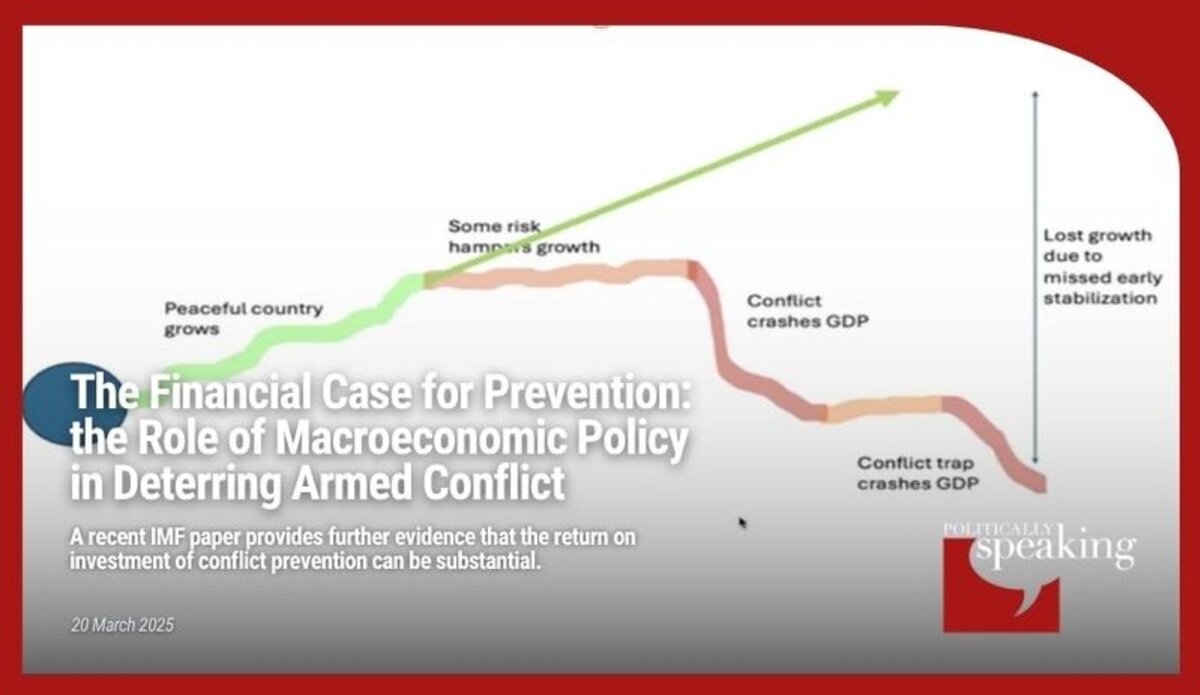

In “The Urgency of Conflict Prevention — A Macroeconomic Perspective,” IMF experts and academics argue that well-targeted macroeconomic policies can reduce the risk of armed conflict in a number of cost-effective ways, with far-reaching results. The IMF paper, prepared as the institution implements its Strategy for Fragile and Conflict-Affected States (FCS), draws on machine learning and dynamic optimization models (analytical tools used in economics to make predictions and solve complex problems) to estimate the potential returns of conflict prevention through economic policy and to simulate how investments in prevention could yield long-run benefits. The paper’s findings show that the return on investment for conflict prevention can be substantial, especially when compared to the costs of conflict.

“Prevention can pay off,” said Christopher Rauh (IAE-CSIC, University of Cambridge, Barcelona School of Economics), who co-authored the paper alongside Hannes Mueller (IAE-CSIC, Barcelona School of Economics), Benjamin Seimon (Fundacio d’Economia Analitica), and Raphael Espinoza (IMF). Speaking at a recent event hosted by DPPA, Rauh said that when they started their research, he and his fellow authors set out to ask, “Why is this the case, despite the very low probabilities of conflict?” The answer, he said, is because of the “potentially huge cost of conflict, which compound due to repeated cycles of violence. Therefore, even low levels of risk warrant great attention.” With that in mind, he said, macro-economic policies can be implemented to help stabilize fragile countries.

Rauh and his colleagues also developed their own methodology, using new technology, to approach the subject. “We used Artificial Intelligence to predict conflict — and simulated what happens if you intervene in a country versus if you don’t — and then looked at its future trajectory.”

Rauh said that the team developed “a dynamic early warning and action model where we forecast future violence”, factoring in conflict damages and an estimate of costs to simulate the future of an economy. The result, he said, answers the question of “what would happen if I had intervened when a country diverted off its good path? How well I can do that depends on how well I can predict future risk.”

The research, he said, found that countries that had not recently experienced violence could expect returns ranging from $26 to $75 per $1 spent on prevention. Nations that had recently suffered from violence could see a return on investment as high as $103 for every $1 spent on preventing future conflict. By investing in prevention early, countries could avert the economic costs of war, including destruction of infrastructure and loss of human capital. Moreover, by addressing the economic grievances that all too often underpin violent conflict, prevention measures can create more stable and resilient societies. “We found that an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure,” Rauh said.

Partnerships between the UN, international financial institutions, and national governments

The “Pathways for Peace” framework, upon which the IMF paper builds, provides a roadmap for translating economic insights into policies. While noting that conflict drivers are context-specific, it identifies common “arenas of contestation” that can drive grievances underpinning violent conflict: for example, related to poverty, inequality and socio-economic exclusion. The IMF suggests that international institutions and regional organizations should work closely with national governments to address identified risks effectively. By creating a coordinated approach that combines financial support, technical expertise, and diplomatic engagement, the global community can help countries address specific challenges and shore up their resilience to external shocks.

Gillian Sheehan, Senior Partnerships Advisor at the Peacebuilding Support Office (PBSO), welcomed the paper’s findings, highlighting that the IMF’s work helps reinforce the case for a “prevention lens” in targeting peace and development investments. She noted that the UN Secretary-General has called for countries to consider establishing national prevention strategies, which international partners can support in a range of ways; as for example, the World Bank does through its dedicated envelope for fragility, conflict and violence. Sheehan notes that “In countries like Chad, Central African Republic and the Gambia, the Secretary-General’s Peacebuilding Fund is working closely with development finance institutions to help Governments define and implement national prevention and peacebuilding plans — while the UN Peacebuilding Commission offers a platform for Governments to share challenges and successes at political level”. PBSO’s Partnership Facility helps catalyse collaboration at country level between UN and IFI teams.

Sheehan especially welcomed the IMF paper’s mention of youth unemployment and social exclusion as drivers of conflict, noting that PBSO works on initiatives aimed at improving the empowerment of young people in conflict-affected regions. By engaging marginalized communities and promoting inclusive governance, PBSO helps build resilience and reduce fragility, with the aim of preventing conflict before it can escalate.

“Conflict prevention requires a shift in policy priorities, focusing on the most fragile states,” said Sheehan. “The cost of inaction is immense, and DPPA’s work emphasizes that early engagement in fragile contexts — whether through diplomacy, mediation, or supporting local peacebuilding efforts — helps reduce the risk of full-scale violence.”