Under-Secretary-General for Political and Peacebuilding Affairs Rosemary A. Dicarlo

Remarks to the Security Council on the Future of Peace Operations:

Key Issues, Opportunities and Challenges in the Context of the Review on the Future of All Forms of UN Peace Operations

New York, 9 September 2025

Mr. President,

Thank you for convening this meeting on the review of UN peace operations mandated by the Pact for the Future.

Since the Council last addressed this topic in July, we have continued our extensive consultations process. Over 40 Member States responded to our call for written inputs and offered ideas and reflections. More than 20 civil society organizations contributed inputs so far. This work continues, with more engagements to come.

One message is clear in these contributions: for eight decades, UN peace operations have been an essential instrument of multilateral action for peace. They have enabled the United Nations to deliver effective responses to critical peace and security challenges. They have saved lives.

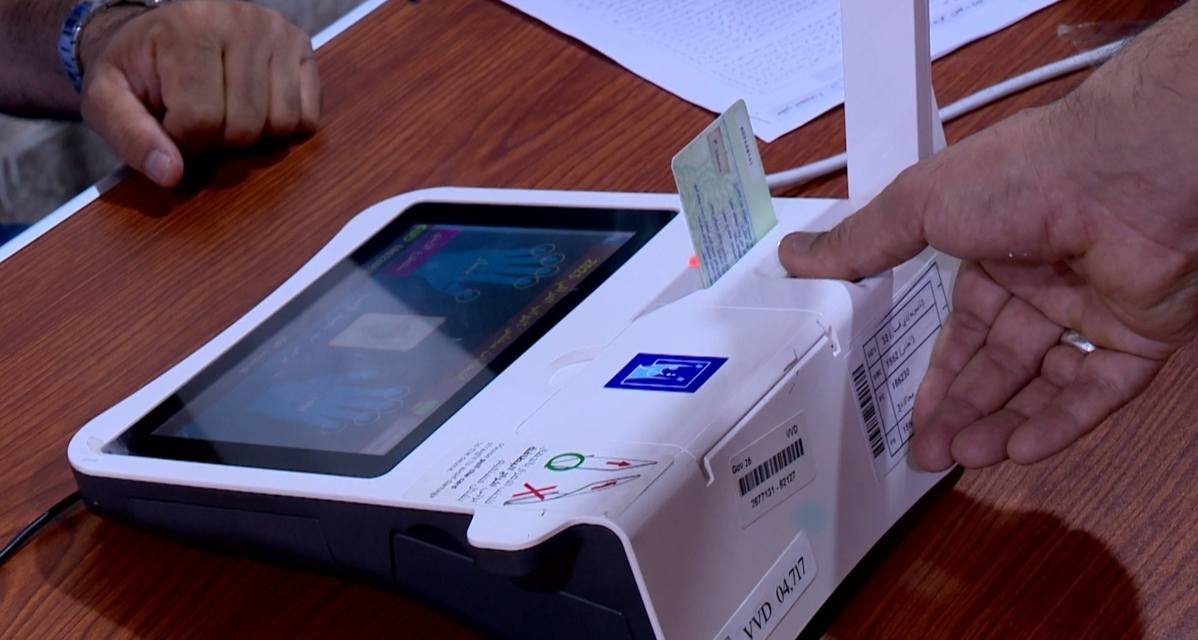

The spectrum of these operations is broad and diverse: it ranges from special envoys, regional offices and expert panels supporting Sanctions Committees to peacebuilding and electoral support initiatives. And it includes observer and verification missions and multidimensional peacekeeping operations that combine troops, police and civilian capabilities.

In many contexts, different types of mission have been co-deployed to provide the mix of peace support needed.

Today, our missions operate in an environment marked by increasing geopolitical fragmentation.

Conflicts have become more internationalized, with the involvement of global or regional actors influencing their internal dynamics. Meanwhile, non-state armed groups continue to proliferate. Many use terrorist tactics or espouse unclear political objectives, challenging traditional peacemaking approaches.

New technologies, from AI to drones, are being weaponized on an industrial scale, increasing both the lethality of violence and the likelihood of escalation. And transnational drivers, such as organized crime, are now a regular facet of the conflict landscape.

These trends have made peacemaking and conflict resolution harder to achieve today.

Opinions diverge among Member States, especially within the Security Council and among host states, on how and to what end peace operations should be deployed, and what the conditions are for their success. This is why a review on the future of UN peace operations is timely.

Mr. President,

To draw lessons for the future, we must learn from the past.

Throughout its history, the United Nations has grappled with intractable conflicts and deep divisions.

Special political missions have been at the forefront of the Organization’s response. From supporting decolonization in Libya and facilitating peace agreements in Central America, to helping South Africa organize its first post-apartheid elections, these missions have supported close to 100 countries across all regions of the world.

They have helped end wars. In Nepal, between 2007 and 2011, our mission helped transform a ceasefire between the Government and the Communist Party of Nepal into a permanent, sustainable peace and political transition.

They have allowed Member States, and the Security Council itself, to find common ground and advance political solutions even at times of high political tensions and deep ideological divisions.

During the Cold War, for example, shuttle diplomacy by the Secretary-General’s Personal Envoy for Afghanistan between Moscow, Washington, Islamabad and Kabul led to indirect negotiations and eventually laid the ground for the 1988 Geneva Accords, which ended the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan.

In order to inform this review of peace operations, we analyzed the history and practice of special political missions deployed since the creation of the United Nations.

Their experiences revealed the following.

First, many of our missions were timebound and targeted. The focus was on a political task, without additional activities overextending the mission’s mandate and focus.

Second, most missions were nimble, easy to deploy, economical to maintain without major overheads and costs.

Third, their mandates were often written concisely and directly manner – sometimes one or two sentences only in a Security Council resolution. This gave the missions clear directions, but also a degree of flexibility in implementing them.

Fourth, missions took great advantage of existing capabilities at Headquarters – from senior officials to substantive experts. These were used as deployable assets, leveraging their political knowledge and diplomatic experience.

Fifth, missions were proactive in using the Secretary-General’s good offices, both through his immediate office and that of his representatives and the UN Secretariat.

Mr. President,

Based on our analysis of past deployments, recent UN reform efforts in peace and security, and consultations held so far, we see three important priorities for designing special political missions today:

First, most of our missions today are deployed in the absence of a comprehensive peace agreement.

Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, peace agreements were the foundation for the work of peace operations. They encompassed the ambitious commitments that conflict parties undertook across multiple areas, from electoral and constitutional processes to security sector reform and transitional justice. Our peace operations, in turn, could be equally ambitious as were, for example, our missions in Cambodia and Timor Leste.

Today, comprehensive peace agreements are the exception, not the norm. Our missions are often deployed in politically volatile situations, sometimes amid ongoing civil wars.

In such situations, the initial goals of our missions should be more limited – such as preventing a deterioration of violence, achieving a ceasefire, or helping a fragile incipient peace process get off the ground. At the same time, they could retain flexibility and adaptability to scale up and seize opportunities at a later stage to advance more ambitious political solutions.

Second, we must continue to improve coordination between peace operations and United Nations country teams.

We must build on the concerted efforts we have made over the years to strengthen the complementarity of our political, development, humanitarian and human rights work.

This is an all-of-UN endeavour, and different bodies, especially the Peacebuilding Commission, can play a critical role. I am confident that the 2025 Review of the Peacebuilding Architecture will help us make additional gains.

Third, the diversity of situations in which our missions are asked to deploy today means that it is essential for mandates to avoid one-size-fits-all approaches.

Accordingly, the Secretariat must provide the Security Council with varied and realistic options for the design of new operations. For this purpose, we will examine how to further improve our planning capacities, enhance creativity and innovation in how missions can be configured, to inform mandate renewals, and to improve transitions.

Mr. President,

There is one fundamental fact that no review, no matter how extensive or ambitious, can change: the failure or weak implementation of mandates is often related to the lack of political support for such operations – in the countries where they are deployed, among regional countries and sometimes in the Council, itself.

We will therefore need to engage with a laser like focus on bringing the emphasis back to the political questions at the heart of each conflict and finding multilateral responses to them.

We look forward to working with you to strengthen the effectiveness of our missions, and to further enhance the trust in their work.

Thank you.